| ||

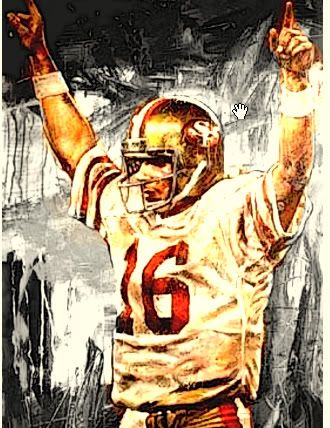

| Sports legend Joe Montana, of half Camunian ancestry |

Borrowed from the archives of 'Poche Parole' (May 2009), the newsletter of the Italian Cultural Society of Washington D.C.

By Terry Necciai

The second of two articles

Railroad construction went at a furious pace through the region, both before and after the Panic of 1873, and gangs of temporary workers were recruited to level the grade and lay the ties and tracks. It is particularly difficult to determine who the workers were and where they came from because of the short term nature of the work and lack of records. However, it appears that the Italian workers found other jobs as a result of the new lines. Railroad development was often justified by the expectation that each line would open up a new area for coal mining. Industrial villages cropped up almost instantaneously as each line was completed. Meanwhile, other Pittsburgh area industries, such as steel, specifically avoided hiring Italians because they thought they were less suited than the Slovaks and other Eastern Europeans for the heavy work required at the larger industrial plants, a prejudice that is on record in some of the surviving trade literature. Because the Italians had an easier time finding jobs in coal mines, they ended up scattered all over the region, in the 500 or more mining villages found within a 100 mile radius of Pittsburgh. Those who brought trade skills with them eventually struck off as entrepreneurs, serving as carpenters, blacksmiths, barbers, tailors, and grocers/fruit handlers, and also sometimes as musicians, writers, or bankers in the new villages.

The Bresciani who came to Monongahela City helped to set off a chain reaction that brought Italians from almost every other part of Italy, boosting the population within and surrounding a very small city that is still 25% Italian-American today. A small group of Calabresi who came in the 1870s may have been the first, followed in the 1890s to 1910s by other Italians from north of Rome, a large group of families from Tuscany, and smaller groups from Umbria, Piemonte, and Venice, and then by large groups from Naples, Calabria, and Sicily, with smaller groups from Abruzzi and Molise. In one of the later waves of immigration, families came from Suisio, an industrial town west of Bergamo, where the dialect was almost the same as that of Brescia. The Italian-Americans in Monongahela whose roots are in the other parts of Italy often refer to the Bresciani and Bergamaschi as the “Patihi, Patahé,” an obscure phrase that the Bresciani had apparently used as a greeting and a shibboleth (though no one from modern day Brescia seems to remember exactly what this phrase means). (My theory is that it could be derived from a word “dialect,” similar to the French “patois.” Or another possibility is “patéser” a verb in the local dialect that means the same as “soffrire” — to “suffer” or to “put up with” someone. Assuming the two words are conjugated forms of a verb, say “patihare” or “patéher,” with an “h” being substituted for a “c” or an “s,” the meaning of “se patahi, pataho” could be “if you speak the dialect, then I will” or “if you put up with [me], then I’ll put up with [you]”)

A small group apparently came about 1886, probably as a gang of young, single men looking for work. Three of the first surnames were: Milani, Pezzoni, and Carrara. Serafino Carrara came to Monongahela from Brescia in ca.1886-88, taking a job in the Catsburg Mine, and by the 1890s, his daughter Maria operated a boarding house for Italian miners on a hillside site overlooking the mine. Undoubtedly, this facility housed many of the Camuni when they first arrived. By about 1915, the Odelli family had a very popular fruit market that later became a peanut and candy store. When Joe (Gio’ann’) Odelli, Sr., rebuilt his fruit stand in 1925, he erected one of the most impressive buildings on Main Street. The Anton family, Bavarian Catholic immigrants who made open flame lamps for the coal miners, took an interest in the Brescians and sponsored the establishment of an Italian Catholic Church in 1904. It was named for St. Anthony of Padua in part to recognize the Antons as the benefactors. The Bresciani were the core group in the congregation. A few years later, in 1913, open flame lamps were blamed for a mine disaster at a mine near Monongahela, taking the lives of 97 men, of whom at least 8 or 10 were from Brescia. Legislation outlawing lamps with open flames after this disaster led to the invention of the safety lamp and then the battery-powered flashlight.

The best known Brescian-American from Monongahela is football quarterback Joe Montana (who played for Notre Dame in the 1970s and the San Francisco 49ers in the 1980s and 1990s). The name Montana is slightly Americanized, apparently from Montagni (he is also half Sicilian, through his mother, Theresa Bavuso Montana).

The Val Camonica is named for the Camunni, an ancient culture of unknown origin that became blended with the Celts of Northern Italy in pre-Roman times. Today, the inhabitants of the valley call themselves “Camuni” (with one “n”). The ancient Camunni left approximately 350,000 rock carvings on the face of the mountains, depicting pre-Roman-era life in the valley. Some are as much as 10,000 years old. To interpret the sparse written passages in the Camuno language that accompanies some of the later carvings, linguists have begun to analyze the peculiarities in the local dialect, which preserves some Camuno characteristics, differentiating it from other dialects of Northern Italy.

The second of two articles

Railroad construction went at a furious pace through the region, both before and after the Panic of 1873, and gangs of temporary workers were recruited to level the grade and lay the ties and tracks. It is particularly difficult to determine who the workers were and where they came from because of the short term nature of the work and lack of records. However, it appears that the Italian workers found other jobs as a result of the new lines. Railroad development was often justified by the expectation that each line would open up a new area for coal mining. Industrial villages cropped up almost instantaneously as each line was completed. Meanwhile, other Pittsburgh area industries, such as steel, specifically avoided hiring Italians because they thought they were less suited than the Slovaks and other Eastern Europeans for the heavy work required at the larger industrial plants, a prejudice that is on record in some of the surviving trade literature. Because the Italians had an easier time finding jobs in coal mines, they ended up scattered all over the region, in the 500 or more mining villages found within a 100 mile radius of Pittsburgh. Those who brought trade skills with them eventually struck off as entrepreneurs, serving as carpenters, blacksmiths, barbers, tailors, and grocers/fruit handlers, and also sometimes as musicians, writers, or bankers in the new villages.

The Bresciani who came to Monongahela City helped to set off a chain reaction that brought Italians from almost every other part of Italy, boosting the population within and surrounding a very small city that is still 25% Italian-American today. A small group of Calabresi who came in the 1870s may have been the first, followed in the 1890s to 1910s by other Italians from north of Rome, a large group of families from Tuscany, and smaller groups from Umbria, Piemonte, and Venice, and then by large groups from Naples, Calabria, and Sicily, with smaller groups from Abruzzi and Molise. In one of the later waves of immigration, families came from Suisio, an industrial town west of Bergamo, where the dialect was almost the same as that of Brescia. The Italian-Americans in Monongahela whose roots are in the other parts of Italy often refer to the Bresciani and Bergamaschi as the “Patihi, Patahé,” an obscure phrase that the Bresciani had apparently used as a greeting and a shibboleth (though no one from modern day Brescia seems to remember exactly what this phrase means). (My theory is that it could be derived from a word “dialect,” similar to the French “patois.” Or another possibility is “patéser” a verb in the local dialect that means the same as “soffrire” — to “suffer” or to “put up with” someone. Assuming the two words are conjugated forms of a verb, say “patihare” or “patéher,” with an “h” being substituted for a “c” or an “s,” the meaning of “se patahi, pataho” could be “if you speak the dialect, then I will” or “if you put up with [me], then I’ll put up with [you]”)

A small group apparently came about 1886, probably as a gang of young, single men looking for work. Three of the first surnames were: Milani, Pezzoni, and Carrara. Serafino Carrara came to Monongahela from Brescia in ca.1886-88, taking a job in the Catsburg Mine, and by the 1890s, his daughter Maria operated a boarding house for Italian miners on a hillside site overlooking the mine. Undoubtedly, this facility housed many of the Camuni when they first arrived. By about 1915, the Odelli family had a very popular fruit market that later became a peanut and candy store. When Joe (Gio’ann’) Odelli, Sr., rebuilt his fruit stand in 1925, he erected one of the most impressive buildings on Main Street. The Anton family, Bavarian Catholic immigrants who made open flame lamps for the coal miners, took an interest in the Brescians and sponsored the establishment of an Italian Catholic Church in 1904. It was named for St. Anthony of Padua in part to recognize the Antons as the benefactors. The Bresciani were the core group in the congregation. A few years later, in 1913, open flame lamps were blamed for a mine disaster at a mine near Monongahela, taking the lives of 97 men, of whom at least 8 or 10 were from Brescia. Legislation outlawing lamps with open flames after this disaster led to the invention of the safety lamp and then the battery-powered flashlight.

The best known Brescian-American from Monongahela is football quarterback Joe Montana (who played for Notre Dame in the 1970s and the San Francisco 49ers in the 1980s and 1990s). The name Montana is slightly Americanized, apparently from Montagni (he is also half Sicilian, through his mother, Theresa Bavuso Montana).

The Val Camonica is named for the Camunni, an ancient culture of unknown origin that became blended with the Celts of Northern Italy in pre-Roman times. Today, the inhabitants of the valley call themselves “Camuni” (with one “n”). The ancient Camunni left approximately 350,000 rock carvings on the face of the mountains, depicting pre-Roman-era life in the valley. Some are as much as 10,000 years old. To interpret the sparse written passages in the Camuno language that accompanies some of the later carvings, linguists have begun to analyze the peculiarities in the local dialect, which preserves some Camuno characteristics, differentiating it from other dialects of Northern Italy.

No comments:

Post a Comment