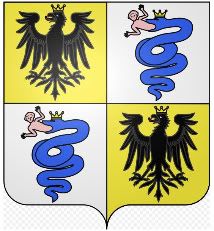

Lombardia, historically the land of the Iron Crown of the Langobards (and later Napoleon), and also known for iron mining in the Valle Camonica. For centuries the valley produced both the raw materials for armaments of war and their design. They did this for whichever government ruled over them, not the least of which was the thousand-year Venetian Empire.

Lombardia, historically the land of the Iron Crown of the Langobards (and later Napoleon), and also known for iron mining in the Valle Camonica. For centuries the valley produced both the raw materials for armaments of war and their design. They did this for whichever government ruled over them, not the least of which was the thousand-year Venetian Empire.

Northern Michigan, also known for iron mining. Lots of it. Although the mining has waned, the place names remain. Iron Mountain, Ironwood, Ironwood Township, Iron River, Iron Belt, Iron Exchange Bank, Ironwood Ridge, and bordering Iron County, Wisconsin, just to give a few examples.

Lost in the history of this region is the fact that it attracted a somewhat sizable number of immigrants from Lombardia. Sizable at least in the percentage of the overall population in this rural region. I had always heard about "Northern Michigan," but the name didn't mean anything to me until I looked closely at a map, and could see that it was almost like a state onto itself, separated from the rest of Michigan by the great lakes. It's a rural area, much of it flatlands, heavily forested, and with a distinct pure northern feel to it. I think when people say the "north woods," they're probably talking about Northern Michigan. I recall looking at an old National Geographic magazine once, and seeing at least a part of this area which was extremely heavily wooded, with the huge tree trunks, mixed with rocky and lush mossy ground cover, and which reminded me of some parts of the wooded Sierra Nevada areas more than the Minnesota or Wisconsin-style wooded flatlands.

I can recall one time, on television, two Italian-Americans, both from one of the major northeast urban areas, referring to "Italians in Northern Michigan," jokingly as being "kind've different." As they laughed, this went right over my head at the time, and I thought that it merely meant that they were "rural people," as opposed to "city people." I suspect that they actually meant that they had visited the area, and found that those "Italians" struck them as being very different. More than mere "city versus country" would suggest. Different faces, different mannerisms. In fact, a different ethnic group.

One center of Lombardian settlement, in and around a century ago, was in Ironwood, Michigan. Ironwood was a mining town founded in 1889. Its population today is only 6,293 (down from 10,000 in 1900), but it is the chief city in that particular part of Northern Michigan. I'm not going to do a profile on this city, as it would get me too much off track, but do take a look at the link, and of nearby "suburbs" like Hurley, Wisconsin, which is directly across the Montreal River from Ironwood in Iron County. The main business strips of these cities remind me of Calistoga, California, or even Petaluma, as far as architecture and old simple beauty. Of course, with a northern flavor to them.

"Ironwood" is also a forest in Norse mythology, from the Poetic Edda, and likely named this due to the large Scandinavian-American population. This also is a remote connection with Lombardia. Another connection is the St. Ambrose Catholic Church in Ironwood, founded in the 1890s, and of the distinctly Lombardian "Ambrosian Rite" of Catholicism, and which is also referred to as the "Milanese Rite."

A excerpt from the Ironwood Wikipedia page under History: "Iron ore was found in the area in the 1870s but it wasn't until the mid 1880s when the arrival of the railroad to the area opened it for more extensive exploration of the vast iron ore deposits. Soon several mines were discovered and opened such as the Norrie mine, Aurora mine, Ashland mine, Newport mine, and Pabst mine. The opening of the mines and the lumber works in the area led to a rapid influx of immigrants both from other parts of the USA and directly from Europe (mainly Sweden, Germany, England, Italy, Poland, Finland)."

Another excerpt from this page under Demographics: "The ancestral makeup of the population were 24.7% Finnish, 17.0% German, 14.8% Italian, 12.6% Polish, 10.4% English and 9.5% Swedish." Anything here under the title of "Italian" is largely Lombardian or similar cultures. A region populated by Germanic or Germanic-influenced peoples, and in a landscape and climate which is very "northern."

The following is from an article entitled 'Ethnic Life in the South Shore Region', which is the region south of the massive Lake Superior. Take a peek at the above link, at the gallery. Like with so many subjects, I wish I could do this more justice, so to speak. There's so much history here. Those Great Lakes are accessable to the Atlantic Ocean, I think, as we can see photographs of ship traffic in them. While poking around Wikipedia in preparation of this article, I looked at the page for Duluth, Minnesota, which is right on the eastern shore of Lake Superior, and in the images there was one beautiful old image of one of those old passenger ships, like the Titanic, coming into the Duluth harbor at twilight. If you didn't know where it was, you would swear it was any ocean port. The immigrants may have even made their way to Northern Michigan mining communities, like Ironwood, by ship.

"Ethnic Life in the South Shore Region

By Greta Swenson

The term “ethnic identity” is used today to describe a feeling of shared heritage and cultural expression found among groups who have migrated and resettled in a “New Land.” In northwestern Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, Swedish, Norwegian, Finnish, Croatian, Slovakian, Czech, Polish, Russian, Italian, Cornish, Irish, German, Lithuanian, and other peoples came to the area to reestablish their families, communities, and churches just before and after the turn of the century. Settlement days along the South Shore of Lake Superior were like a bustling League of Nations, freshly organized and economically booming.

The settlers brought with them and developed a rich ethnic history in the region. But the rich, diverse cultural life brought by the early settlers did not end with that history. Those cultures interacted, intermarried, and adapted to the economic and climatic necessities of the northern winters. They transmitted their traditions to the succeeding generations. Today in the South Shore region, ethnic expression is a part of everyday life. We can see indications of that life on the streets, in the grocery stores, and in other public forums. Private means of expressing who we are, are also part of ethnic life in the South Shore region. This life is expressed in a variety of ways. In order to explore the ethnic life of the region, we will first take a look at the settlement days.

Settlement

Settlement

European presence along the South Shore of Lake Superior began with the voyageurs and missionaries as early as 1659. Settlement of the land and towns in this region, however, did not occur until a period from 1840 to 1920, during the second large wave of immigration to the United States. People migrated to the South Shore region, as to other parts of the country, because of the need for labor and raw materials to support the rapid industrial expansion taking place in the United States. They left their old homes because of a lack of land, work, or idealogic freedom in many of the European countries.

These two urges opened wide the gates of passage from Scandinavia and Eastern and Southern Europe to “New Worlds.” The first large group of new immigrants to come to the region were the Cornish. They were recruited to work in the mines of the Copper Country in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. When those mines opened in the 1850s and ‘60s, experienced Finnish copper miners working in Norway were also recruited and imported by the mining companies. Following company recruitment, immigration to the mines increased rapidly. Building of the railroad for shipment of the ore was one reason for the increased migration.

In addition, immigrants wrote “American letters” to family and friends in the Old Country and other parts of North America, telling them work was available and providing an address to which to come. The Cornish and Finns ere followed by Scandinavians, Italians, Slavic groups from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Germans, and several other groups seeking work. Many of these immigrants to the region had already migrated to North America and were working elsewhere. Twenty years later, the Gogebic Iron Range mines opened up, beginning full production when the railroad was completed to the Ashland, Wisconsin docks in 1884.

At the same time, lumber companies were cutting northern Wisconsin’s an the Upper Peninsula’s white pine forests in order to supply building material to the mining operations and to the rest of the rapidly expanding young nation. In the 1890s, brownstone quarries opened along the South Shore. Work was abundant; the region was booming. Ashland, Wisconsin, in 1900, had a population of 13,000, its waterfront included approximately 11 ore docks, 13 to 18 sawmills, a pulp mill, and a blast furnace. By World War I, the timber had been “cutover” – nothing but stump acreage remained of the giant white pine forests.

Agricultural settlement in the area was then actively encouraged by several agencies, including lumber companies, the state governments, and private land investors. New groups of migrants came to the region to work the land. Advertisements, such as this one of the James Good Land Company in Ashland, Wisconsin, were published in ethnic language newspapers printed in the United States. This particular advertisement was published in the Czech language and widely circulated throughout the United States. Slovaks and Czech-speaking Bohemians who were working in the coal mines in Oklahoma, or slaughterhouses in Iowa, saw an opportunity to own their own land and headed north.

They settled the community of Moquah, Wisconsin, southwest of Ashland. Others did the same: advertisements were also circulated in Polish, Hungarians, Croatian, Finnish, and the Scandinavian languages. The boom continued. After strikes in the Minnesota and Michigan iron mines in 1907, 1913, and 1917, Finns, Croatians, and others left the mines and moved out to the stump acreage to settle the land of the South Shore region. This sign from one of Ashland, Wisconsin’s early banks reflects the rich ethnic diversity of those early boom years along the South Shore. It also reflects the major motivation for migration to the area: opportunity to economically better ones and one’s family’s condition.

“We can send money to the Old Country” the sign proclaims in Swedish, Finnish, Polish, Slovak, German, Hungarian, and Russian. Life in the booming frontier area was multicultural. The settlers brought with them their diverse languages, religions, foods, and customs. People bonded together for mutual support, mingling with their neighbors. Societies like this Italian group were formed or mutual benefit and to supply social interaction. Most groups soon established a church, organized according to language and culture. In 1907 in Calumet, Michigan, for instance, six Catholic churches were active: Polish, Italian, Slovenian, Croatian, French, and one general.

In Ashland, Wisconsin, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, Finnish, Swede-Finnish, and English Lutheran churches has also been organized. Several ethnic language newspapers were published in the region during those early years, providing the settlers a contact with others of their group throughout the world. In the public arena, the rich cultural diversity of the region’s settlement days contributed to entertainment. Members of the Swedish Glee Club celebrated Midsummer’s Day with a picnic, while Moquah residents formed a Slovak Dance group, and members of the Croatian Fraternal Union played tamburitza music.

At home, more private expressions of ethnic identity can be traced through the words of settlers. Oral histories, diaries, songbooks, and newspaper articles reveal active ethnic identities among the settlers. Evidence of home-centered expressions of cultural roots can also be found in museums – a krumkake iron from a Norwegian woman’s kitchen, or a collection of Swedish wood carvings from someone’s living room. Family celebrations, such as weddings and funerals, varied from group to group, but were also mixed, as people began to marry into different cultures.

Regional Mixture

Ethnic groups settled often in enclaves – a large Finnish population, for instance, in the township of Oulu, Wisconsin, or Italian families in “The Flats” between Ironwood, Michigan and Hurley, Wisconsin. Both at work and at play, however, people did rub elbows with their neighbors. Musicians in the various communities, for instance, traded tunes and instruments. Folklorist Jim Leary described the life of one musician as “How a Pole learned a German tune from a Norwegian accordionist while playing an Italian instrument at a Swede’s tavern.” Ethnic expression along the South Shore was a part of everyday life for the settlers. They practiced their own traditions, and learned new ones from their neighbors. This diverse mixture of ethnic traditions is visible in the region today.

Current Life-Public

Current Life-Public

Some very public indicators of the current ethnic life along the South Shore exist today. Signs such as that for Koski Korners outside of Marquette, Michigan, or the several public saunas in the city, indicate immediately to the causal observer that segments of a Finnish heritage are still active in the community. The churches remain as landmarks to the ethnic neighborhoods, and in some cases indicate the unique mixture of ethnic religion with regional economy, as does this copper-domed synagogue in the Upper Peninsula’s copper country. Some ethnic halls and societies are yet active, other, as one Swedish-Finn put it, are no longer necessary, since insurance companies have replaced them.

Musicians, older and younger, are still active in the region. Art Moilanen still plays Finnish polkas and schottisches in Mass City, Michigan every Saturday night. In the Bohemian and Slovak settlement of Moquah, Wisconsin, entertainment at an annual hunters’ ball is provided by a local band, the Polka-Teers. Members of this band are of Slovak, Croatian, and Polish descent. They play music from each of those cultures, as well as more modern pieces from artists like Johnny Cash, and a Finnish schottische now and then. Records stores carry current ethnic artists, and local jukeboxes may feature Croatian, Finnish, or Italian numbers.

If you walk into a grocery store in Ashland or Hurley, Wisocnsin; Ironwood, Hancock, or Marquette, Michigan, just before Christman, you will be greeted with a sign such as this in Ironwood’s Jack’s Food Store. Holidays are a special time for many ethnic groups, and no Swede, Norwegian, or Finn would be caught celebrating Christmas Eve without lutfisk. Other items in the grocery store are surprising to the casual observer only because they are not in specialty sections. Swedish headcheese, or sylta, is next to the bologna. In the Italian area of Ironwood-Hurley, shelves are lined with pasta. Bakeries feature such items as Scandinavian “toast,” or rusks, and Finnish breads.

Finnish restaurants feature Cornish pasties, a regional symbol of the settlement mixture. As one resident of the Upper Peninsula once commented about the pasty, “They were brought by the Cornish, made edible by the Finnish, but the best ones made around here now are made by an Italian.” Down the road, Billy Trolla, a second-generation Italian grocer, caters to the special needs of second-, third-, and fourth-generation Italian families. Community events nearly always involve some sort of ethnic expression in the South Shore region, whether Croatian cabbage rolls are served at a wedding, or Italian-American communities. The Swedish Lutheran Church in Ashland, Wisconsin each year celebrates St. Lucia Day before Christmas, and Finnish communities in the region stage annual Johannus, or Midsummer’s, celebrations.

Current Life-Private

While there are visible landmarks and customs which tell us about an active ethnic life along the South Shore, it is inside people’s homes – in their kitchens, attics, daily rituals – that the ethnicity of the region is most expressed. Private expressions in the daily lives of area residents have been passed along, sifted out, and chosen as favorites symbols of ethnic identity. No tradition is so strongly continued in the ethnic homes as are those of food. If we peek into the kitchen of Irene Lunda Novak, a Czech-speaking Moravian from the Moquah, Wisconsin community, we will likely find her baking special sweet breads and kolache to have on hand for coffee time. Irene learned to make kolache from her mother, as did her sister, Agnes.

They now make them differently from each other, but, as Agnes says, “They taste the same.” Rose Tody Kriskovich, who lives only a few miles from the Novaks, is of Croatian descent. What Rose pulls out of the freezer when visitors stop in at coffeee time is strudel made from a distinctive “stretch dough” her mother used. Here her niece, Marilyn McKay, learns to prepare the strudel the way Rose did – by helping. Rose Stella Longhini’s parents migrated to Ironwood, Michigan from the Abruzzi region of Italy. From her mother, Rose learned to prepare varieties of Italian pastries and “cookies,” items she prepares and stores in her freezer, so they are always “on hand.”

Agnes Raspotnik Oreskovich, of Slovenian descent, cuts a different pastry for the coffee plate: a rolled walnut bread called “potica.” Scandinavian-Americans in Hancock, Michigan may prepare rosettes, while Polish-Americans in Ashland, Wisconsin spend a great deal of time and effort making pierogi for special occasions. But, food isn’t the only private form of expressing one’s ethnic heritage. Once we set food inside Irene Novak’s kitchen, we will discover more non-public symbols of her identity in other parts of her home. In addition to special kitchen utensils used to prepare Czech sweet breads, Irene has safely kept away in a truck hand-embroidered headdresses sent to her by her cousins in Moravia when she was a girl.

In the home of Agnes and Joe Oreskovich will be found representative hand-crafted items from Yugoslavia. Mrs. Norman Burnside include in her decor symbols of her Norwegian ancestry, while Vern and Naima Sandstrom proudly display a symbol of their multiple identities: Swedish, Finnish, and American flags. Another symbol of their ethnic identities is hidden away in the basement: the ever-present Finnish sauna. Ethnic life in the region stems from the settlers’ rich, diverse cultural heritages, heritages which also have mingled together to produce distinctive regional expressions. Past and present, public and private, traditional and adapted, the diversity of those ethnic expressions adds a uniqueness to life in the South Shore region.

Credits

Produced by Special Student Programs

Northland College

Ashland, Wisconsin 54806

Script by Greta E. Swenson

Visuals by Sue Ellen Smith, James P. Leary and Greta E. Swenson

Funded with a grant from the Ethnic Heritage Studies Program

U.S. Department of Education, directed by Stuart Lang.

Narrated by Cynthia Soucheray-Luoma

Music by Ray Maki, Olavi Winturri, Bill Hendrickson, The Voyageurs, George Noisianen, Jerry Novak, St. Mary's Russian Orthodox Church, Gogebic Range Tamburitzans, Rose Swanson & Friends, Art Moilanen, Saron Lutheran Church, Tom Marincel, Bruno Synkula, and the Bethany Swedish Baptist String Band.

This program is a result of hospitality extended by the people and organizations of the South Shore region."