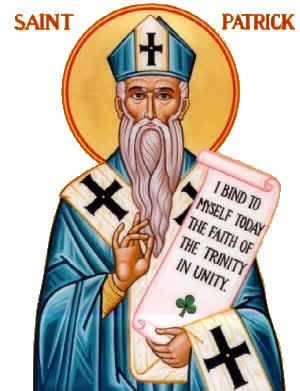

Saint Patrick, the Irish Druids, and the Conversion of Pagan Ireland to Christianity: Part 1

Saint Patrick, the Irish Druids, and the Conversion of Pagan Ireland to Christianity: Part 1By Bridgette Da Silva - StrangeHorizons.com - July 27, 2009

The patron saint of Ireland, Saint Patrick, is often credited with kicking all the snakes out of Ireland. Countless works of art have depicted the bearded saint crushing serpents under his feet, and pointing to the distance with his staff as if to banish them from his sight. But how is one to reconcile this story with the fact that there has never been any evidence of these reptiles living in Ireland in all its history? Some scholars contend that the snakes were originally symbols for Irish druids. Serpents are thought to have been important in the Celtic spirituality of the pagan Irish, and the druids were the keepers of that faith, acting as priests and priestesses.[1] So if indeed the druids are the snakes in these stories, and Patrick is supposed to have driven them forth from their homeland, can we suppose that there is any truth to the idea that Patrick had a hand in banishing the druids from Ireland? Just who were these druids whom Patrick is said to have expelled?

In addition to driving forth the serpents from the land, Saint Patrick is also said to have been the first man to introduce Christianity to the Irish. If this is true, what exactly was the nature of this conversion?

Muirchu maccu Machtheni was an Irish bishop who wrote Patrick's hagiography, The Life of Saint Patrick, during the seventh century, two hundred years after Patrick's death. This set of stories colors people's understanding of the saint even today. Muirchu wrote that Patrick was the driving force behind the annihilation of the Irish druids. Two of his stories illustrate this claim particularly well. The first deals with Patrick and his former master (Patrick had been sold into slavery from Britain to Ireland at sixteen). The other concerns a confrontation between Patrick and the pagan king Loiguire, along with Loiguire's court druids, at the Hill of Tara in northern Ireland. The Patrick in these stories demonstrates behavior not thought typical of a Christian bishop. Instead of possessing the traits of patience and forgiveness, Patrick is shown as vindictive, and he succeeds in a quest to punish his enemies with the help of the Christian God.

Both of these stories take place after Patrick had been ordained as a bishop. He and a few of his followers supposedly went back to Ireland with the goal of converting the pagan Irish to Christianity. The first place Patrick went on this journey, according to Muirchu, was to his former master Miliucc in order to buy his freedom, for technically Patrick had run away and never paid his former master to become a freedman. However, when Miliucc heard that Patrick was on his way to visit, he thought that Patrick meant to convert him to Christianity by force: "When Miliucc heard that his slave was about to come and see him, in order to make him accept, forcibly as it were, a way of life against his will at the end of his days . . . the devil put it into his mind to seek death of his own free will in fire" (Bieler 81). So Miliucc burnt himself along with all of his possessions. This was a common act of pagans "when faced with inevitable defeat" (Hopkin 41). How did Patrick react to this suicide? He cursed him. Muirchu quotes Patrick as saying,

[T]his man and king, who chose to burn himself in fire rather than believe at the end of his life and serve eternal God . . . none of his sons shall sit on his throne as king of his kingdom in generations to come; what is more, his line shall be subordinate forever. (Bieler 81)

So it seems that indeed it was Patrick's intention to convert Miliucc to Christianity, and the bishop was angry simply because Miliucc had died a pagan instead of a Christian. If one suspects that this reaction is a bit odd for a man of Christ, what is even stranger is Patrick's confrontation with the pagan King Loiguire and his spiritual leaders, the druids.

Muirchu claims that the High King Loiguire celebrated a pagan holiday on the day that Christians celebrate Easter. However, scholars think that Muirchu changed the date of the pagan Beltane festival from May 1 to coincide with Easter in order for the story to make sense (Ellis 76). Loiguire and his druids lived on the Hill of Tara. The druids and the nobility gathered at Loiguire's palace in order to "celebrate with many incantations and magic rites and other superstitious acts of idolatry" (Bieler 85). On that day, pagan custom stated that no fire should be lit in Ireland before the sacred fire was kindled at the palace at Tara (Hopkin 42). Patrick, however, had no love for this custom, and deliberately lit a fire on the Hill of Slane before the fire was lit on Tara. King Loiguire could see this act of disrespect from his palace and gathered his counselors to discuss the matter. According to Muirchu, the druids prophesied that if the fire of Slane were not put out that night, then,

it will never be extinguished at all; it will rise above all the fires of our customs, and he who has kindled it on this night and the kingdom that has been brought upon us by him who has kindled it . . . will overpower us all and you, and will seduce all the people of your kingdom, and all the kingdoms will yield to it, and it will spread over the whole country and will reign in all eternity. (Bieler 87)

[Left: On the Hill of Tara stands a Lia Fáil or Stone of Destiny, a pagan symbol of royal power. In myth, the stone had otherworldly origins, and it would shout when touched by a rightful king.]

[Left: On the Hill of Tara stands a Lia Fáil or Stone of Destiny, a pagan symbol of royal power. In myth, the stone had otherworldly origins, and it would shout when touched by a rightful king.]Essentially, the druids told their pagan king that if they did not stop the actions of Patrick that night, then Patrick would supplant the pagan religion and replace it with the newer Christianity. Of course, King Loiguire was not happy with this idea, so he set off with a number of his druids to stop this act of treachery. The story goes on to describe how the druids confronted Patrick for his misdeeds. Faced with these disgruntled pagans, Patrick converted one instantly, threw another druid up in the air with the power of God and crushed his skull against a rock, and summoned an earthquake to kill the majority of the rest. After this, Loiguire made an escape by pretending to be a pious Christian, but that did not stop Patrick and his followers from bursting into Loiguire's palace the next day when the pagans were feasting for their celebration. Patrick did this "in order to vindicate and to preach the holy faith at Tara before all the nations" (Bieler 93). This is when Patrick and the druids engaged in a magical contest to see whose skills and religion were superior. Once again, the pagans suffered fatalities and lost the contest. "For at the prayer and word of Patrick the wrath of God descended upon the impious people, and many of them died" (Bieler 97). Patrick continued on to tell King Loiguire, "If you do not believe now you shall die at once, for the wrath of God has come down upon your head" (Bieler 97). Indeed, this "convert or die" proclamation convinced the pagan king that "[i]t is better for me to believe than to die" (Bieler 97).

Who were these pagans and druids who suffered much at the hands of Muirchu's Saint Patrick? Were the Irish pagans truly evil? Did people honestly believe that the druids possessed great magical powers, such as the ability to call down snow and darkness at will?

To begin, one must be aware that no one really knows much about the Irish druids. Peter Ellis says in his book The Druids that "one person's Druid is another person's fantasy" (11). Ellis continues on to note that the druids were forbidden by religious law to write down any of their learning, lest it fall into the wrong hands. Most of what we know about them comes from sources innately hostile to the druids, namely the Romans who conquered them in Britain in the first century AD (Ellis 13-15, 32).

Rather than being purveyors of spells and magic, the Irish druids were a learned class that fulfilled many functions in ancient society, from carrying out priestly duties (namely at pagan holidays and festivals) to acting as "philosophers, judges, teachers, historians, poets, musicians, physicians, astronomers, prophets, and political advisors or counselors" (Ellis 14).

The word "druid" is related to dru-wid, which means "oak knowledge." Not only did the oak figure in to the spiritual life of the druids, but Ellis proposes that the oak symbolized survival itself, as it supplied many essential substances, including wood for kindling and shelter, and acorn flour for bread. Ellis thinks that thousands of years ago, those who knew about the properties of oaks were said to have "oak knowledge," and thus they were considered part of the learned class, as they were the ones who possessed the knowledge that would help the Celts survive (39-40).

There were three primary classes of druids: the bards (singers and historians who passed down knowledge through song), the prophets, and the druids who studied philosophy and nature (Ellis 51). Druids could marry and have children if they wished, and many druids were actually women, called ban-drui or druidesses. Saint Brigit of Kildare is said to have been brought up and educated as a ban-drui before converting to Christianity.

Though the Irish druids refrained from leaving written records of their practices, what is clear is that druids in early Celtic society were not considered mere magicians. Instead, they comprised an entire intellectual class and performed necessary functions in Irish society.

Throughout history, there have been cases of one religion imposing itself on another by force. Was the conversion of Christianity in Ireland another such instance, as Muirchu would have us believe? Magic and prophecies aside, Muirchu's stories imply that Patrick came to the island with a troupe of men to convert the "heathens" to Christianity. Ostensibly, in the course of this mission, there were some bloody encounters between Patrick and those of the older pagan faith, especially the upholders of that faith, the druids. How well do these stories, written two centuries after Patrick's death, represent reality?

To answer this, it is important to note that scholars make a distinction between the mythical and the historical Saint Patrick. Muirchu and others after him are responsible for inventing the character of the mythical Patrick. Muirchu's Patrick is a shaman who is familiar with the workings of magic and miracles, and is not above cursing and killing his enemies in the name of Christ. He scorns the druids and their pagan faith because he believes that it is a false faith. Thus, he can justify his actions toward those who refuse the word of God. The stories of the mythical saint can certainly tell us much about the context of the times in which they were invented, the seventh century AD, but what can they tell us about the truth behind the conversion of the Irish to Christianity? Is there any historical basis for these "convert or die" tales?

To best be able to consider the character of the historical Saint Patrick, it is wise to consider his entire pilgrimage and dealings with the Irish. There is a manuscript by Patrick called the Confession, written in the fifth century AD, in which he relates some of the events that meant much to him in life. He describes his first interaction with the Irish, which could indeed be considered a bad one: at age sixteen, Patrick was captured in an area of Britain called Bannaventa Taburniae by Irish raiders, and was subsequently sold into slavery across the sea. (No one has been able to locate this settlement, but scholars assume it is on the west coast.) In Britain, he had been part of the landowning upper class. His father was a deacon and his grandfather was a priest. (The clergy had less strict notions of celibacy in that period.) Yet Patrick admittedly was not a faithful Christian. He said, "I did not believe in the living god, no, not from my infancy, but I remained in . . . unbelief" (Thompson 7).

.

No comments:

Post a Comment