Apparently this article is a part of a series about Hebrew/Jewish history. Like all articles, which are at least partially from either an specific "ethnic interest" or a particular cultural point of view (Anglo-Saxon, Jewish, Southern Italian, etc.), I hold a slight skepticism. This could be in the form of something being exaggerated, out of proportion, false paradigmed, or out of comparative logic.

Apparently this article is a part of a series about Hebrew/Jewish history. Like all articles, which are at least partially from either an specific "ethnic interest" or a particular cultural point of view (Anglo-Saxon, Jewish, Southern Italian, etc.), I hold a slight skepticism. This could be in the form of something being exaggerated, out of proportion, false paradigmed, or out of comparative logic.This article seems on the level. I was particularly interested in the overview of the Brescia/Camonica region from this particular scholarly and thoughtful point of view. In other words, it's more thorough than an encyclopedia, and still short enough to be considered an overview introduction.

This material is copyrighted. However, the Hebrew History Federation is a non-profit organization, run by non-salaried volunteers, and certainly this blog is not for profit, so I assume that there will be no problems. Full credit for this work goes to the following:

'The Jews of Brescia: Iron and Star of David' ©

Samuel Kurinsky (author)

Hebrew History Federation Ltd.(www.hebrewhistory.info)

345 West 58th St., #9M

New York, NY 10019

E-mail: info@hebrewhistory.info

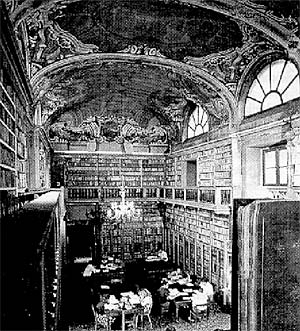

[Above Right: The first of a set of 34 massive tomes produced for the church in 1774, housed in the Querignano library of Brescia. They purport to be a complete compendium of Judaic religion, rites, customs, institutions, culture and literature. They contain thousands of documents from Judaic and other sources written in Hebrew, Aramaic, Latin, and Italian. The material housed in the Querignano library rarely has been looked into for the more than two centuries of their existence. Father Franco Bontempi, a Catholic priest, has delved into such hitherto overlooked archives to document the hidden history of the 2000-year Judaic contribution to the culture and industry of North-central Italy. Illustration by courtesy of the Querignano library]

**************************************************

The Jews of Brescia:

Iron and Star of David

Fact Paper 34

© Samuel Kurinsky, all rights reserved

* The Jews of Brescia: Iron and Star

* "Don Franco's" Research in Valcamonica

* Etruscans and Semites in Valcamonica

* Fire and Water: Industry Elements

* The Querigniana Library

* The Kaufman Collection

* The Gonzaga Connection

* Printing and Papermaking

* The Martinengos and the Jews

* Bandiera Rosso; Bandiera Verde

* Notes

The Jews of Brescia: Iron and Star

Documentary evidence has revealed that at the turn of the Common Era a Jewish woman, Annia, a freed slave, was actively involved in the iron industry of northern Italy.

The evidence was presented by Father Franco Bontempi of the St. Francis Cultural Circle of Brescia, Italy, at an exhibition in New York co-sponsored by the Istituto Italiano di Cultura and Yeshiva University Museum. The exposition featured research done by Father Bontempi in the mountainous region northwest of the city of Brescia. The Jewish presence in that area, and the association of the Jews with the ancient iron, pottery, glass, printing, paper, textile, and stringed instrument industries, was discussed by Father Bontempi at the Museum, then at the Istituto, and a third lecture at New York University's Italian Cultural hall.

Father Franco Bontempi is a Catholic priest charged with a Brescian parish. He is an enthusiastic scholar who devoted many years to documenting the Jewish presence and activities in the north-central sector of Italy. Convinced that the Jews had an important and salutary impact upon Brescian culture and industry from pre-Roman times through the Renaissance, he assembled an array of archaeological, documentary, and historical evidence to support his thesis. He demonstrated that the important Jewish contribution to the technological development of the Brescian area was heretofore overlooked and underrated.

His sympathetic perspective on Judaism may be rooted in the fact that his mother (nee Modena), was of Jewish origin. In addition, the Bontempi family were, until the sixteenth century, Jewish merchants of importance.

The Alpine region above Brescia is the only place in Italy where iron (and copper) ore is found in sufficient quantities to be mined. The region was therefore of vital importance from pre-Roman into modern times, when other, more productive European resources caused a decline in the iron industry. The area still, however, boasts of a major metallurgical industry. Towns in the hills above the neighboring city of Bergamo are replete with foundries and factories producing a wide range of metal products from hinges to cannons. The mountains around Bergamo offer spectacular vistas, but heavy pollution and frenetic industrial activity discourage tourism.

[Left: A tombstone fragment of the early Roman period found in Brescia. The inscription refers to the patroness of the "Brixia" synagogue. Another such tombstone is inscribed to an "archisynagogue." Photo by the author, courtesy of the Santa Giulia Museum, Brescia.]

[Left: A tombstone fragment of the early Roman period found in Brescia. The inscription refers to the patroness of the "Brixia" synagogue. Another such tombstone is inscribed to an "archisynagogue." Photo by the author, courtesy of the Santa Giulia Museum, Brescia.]The mountains around Brescia, however, still retain a pristine beauty. Lake Iseo, nesting jewel-like among forested hills, was the site of an ancient Jewish cemetery. Three of the inscriptions found in the ruins of the cemetery provide definitive information about its existence.

Additional Jews arrived as slaves in the early Roman Imperial period and subsequently became a viable free community. It is one of many previously unknown and unheralded Judaic communities that practiced their technological expertise amid primitive surroundings. It shares with Aquileia the distinction of being another noteworthy community absent from the Encyclopedia Judaica and from current atlases of ancient Judaic communities.

One gravestone inscription bears the name Annia Juda Liberta, which translates to "Annia the Freed Jewess," that is, freed from slavery. The stone is in the form of a stele, and contains a still legible, detailed inscription which provides highly instructive information. Deference is given to Junone, the pagan god of water and iron venerated by the local tribes, in thanks for the ferric largesse provided. The dedication indicates that due consideration was being shown to the religion of the local tribesmen by thanking them through their god for the valuable ores being taken from their mountains.

The dedication indicates that the Roman Gods had not yet penetrated that region, and helps establish the date of the cemetery to as far back as 50 BCE.

The existence of a synagogue is evidenced by a second cemetery inscription, in which the name Celia Paterna Mater Sinagogae Bruxianorum appears, informing us that the woman Celia Paterna had been a sponsor of (or donor to) the synagogue of the region of Brescia.

The name of a third inscription verifies the existence of a synagogue at this early time. The title: of the deceased, archisinagogo, designates him as the head or deacon of the synagogue to which the cemetery pertained.

The early date of the inscriptions is reinforced by the fact that the Greek, rather than the Latin alphabet is employed in several inscriptions.

The existence of a substantial Judaic community is again made apparent by the exposure of many small mosaic floors in the cemetery's periphery. The floors include the motif of the nodo di Solomone, "Solomon's knot," as it is referred to in Italian sources, and as "Solomon's seal" in other references. This design identifies the residents of the houses as Jewish. Readers of the HHF Newsletters will recall the appearance of this symbol in a Jewish context in Aquileia, Monastero, Vercelli, Ostia, and Sicily.

One large rock in the area features a Nodo di Solomone in the graffiti incised upon its face.

The area in which cemetery and the mosaic floors were found was known throughout the ages as the Posto di Schiavi, or "The Place of the Slaves."

It is significant that the pass which leads from the area of Lake Iseo to that of the valley from whose mountain sides iron and copper were mined, is still labeled on current maps as the "Passo degli Ebrei," or "The Pass of the Jews."

Evidence of pottery manufacture by Jewish community members was also found. It will be recalled that the HHF was instrumental in proving that the Jews of Kfar Hananiah and Shikhin were expert industrial potters by funding the analyses of pottery shards from those Judahite communities. It would indeed be interesting to determine if the style and technology used in manufacturing the Brescia earthenware of the same period bears a relationship to that of Kfar Hananiah and Shikhin!

Is it mere coincidence that the name of the freed slave on the cemetery stele was Annia, a Greek transcription of the Hebrew Hananiah?

Thus the evidence gathered by Father Bontempi provides overwhelming proof that an active Judaic community with a synagogue and a cemetery existed around lake Iseo in the iron-mining pre-Alpine region of northern Italy at the turn of the Common Era.

Research on this ancient Judaic community was but a part of Father Bontempi's extensive research and writing about the Jewish presence in the province of Brescia and in the surrounding provinces. The existence of non-native mulberry trees evidence the introduction of sericulture by the Jews. Sericulture (the production of silk) was an exclusively Judaic art at the time.2

There is also evidence that the introduction of the production of stringed instruments in Cremona was yet another seminal Jewish contribution to the area. The first renowned producer of the violin in its modern form, Amati, is said to have been of Jewish origin! Father Bontempi states that there is also evidence that the inventor of the famed varnish that presumably gives the Cremona violins their rich tone was likewise a Jew.

The introduction of the printing industry into the area by a Jewish family fleeing oppression in Germany is another historically significant technological landmark of the region. The name of the family became Soncino, after the town south of Brescia where they established one of the earliest and most renowned printing establishments.

The title of the exhibitions curated by Father Bontempi is the same as that of his book, Iron and Star, a reference to the iron industry and the star of David. The subtitle, Jewish Brescia in the Renaissance Italy, refers to this continuing history.

Another important book by Father Bontempi, Bienno, History, Society, and Economy, elaborates his theory on the introduction of Iron Age technology into the region of by peoples from the East.

"Don Franco's" Research in Valcamonica

Don Franco, as Father Franco Bontempi is lovingly referred to by admiring friends throughout the region, invited Dr. Pauline Weiss and me to examine his evidence at first hand. We attended affairs, we visited pertinent sites. As a consequence of his influence we were given carte blanche access to the archives of the region. I was assigned to lecture to two of Don Franco's classes, one for students and the other for teachers. I was likewise honored to address the partisans who fought in the Alpine region against Nazi contingents. The occasion was a commemorative affair held yearly high atop a mountain at the grave sites of those who had fallen in battle.

We were chauffeured daily by two of Don Franco's friends, and by the Mayor(ess) of Lusine, one of the towns in the area

Exposure to the history of the Bontempi family was an education in itself. They lived in Valcamonica (the Valle Camonica), the valley of the ancient Cammuni people. It is a spectacular, exquisitely beautiful valley between two craggy Alpine mountain ranges east of the city of Brescia. The valley encompasses the jewel-like lake Iseo, and stretches from the Po Valley up along the Oglio River to the Swiss border. The Bontempi family dates back the 12th century under that name, and has been traced back to about 1000 CE.

Two murals once decorated a former Bontempi family palazzo in Lusine, dating to the 14th century. They were removed from the family home and are now exhibited in the city hall of the town. One of the murals, some 40 feet long, contains the larger-than-life figures of five secular sages. King Solomon is prominently featured in the middle between Aristotle, Socrates, Solon and an old wise man of the mountains. The selection of characters reflects the intellectual concerns of the family. Solon (c.640 -c.559 B.C.E.), was an Athenian merchant, lawgiver and poet who, when appointed to reform the constitution, set free all people who had been enslaved for debt. He also admitted a fourth class to the Ecclesia, thus laying the foundations for Athenian democracy.

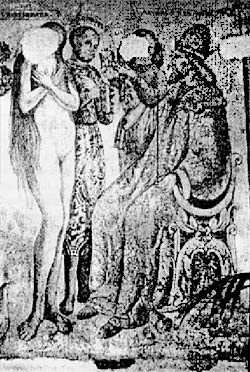

The second mural, fourteen feet long with life-size figures, illustrates Esther being crowned Queen by King Aheuserus on the right. The former Queen and the evil figure of Haman being banished are pictured on the left.

Don Franco's Judaic origin was undoubtedly one of the motivations that impelled him to delve further into the history of the Jews of the Brescian region In a third book, published as Economia del Ferro, research on the history of the iron industry in Valcamonica from the 15th to the 19th century, he documents the evidence that Jews were involved in the industry in an early period.

The evidence uncovered about the hitherto ignored contribution of the Jews to the culture and industry of the province of Brescia, has been presented by Don Franco in Italy, the United States and Canada, through his lecture and exhibition entitled Ferro and Stella (Iron and the Star of David).

[Right: A detail of one of the 14th century murals from the Bontempi ancestral home in Bienno, Italy, showing a very virginal Esther being crowned queen. It is now displayed in the town's city hall. Photo by the author.]

[Right: A detail of one of the 14th century murals from the Bontempi ancestral home in Bienno, Italy, showing a very virginal Esther being crowned queen. It is now displayed in the town's city hall. Photo by the author.]"When I started my research for the show," wrote Don Franco, "I heard it said that everything [on the subject of Jewish presence] had been already unearthed, and there was nothing was left to add. From the end of the eighteenth century there were studies made about the presence of the Jews in Brescia. [It was said that historians] Glissenti, Zanelli, Gamba, Guerrini, had already taken all the sources into consideration. All the same, this previous research had severe limitations. In the first place, they did not know the Hebrew language, and consulted only documents written in Latin or Italian from Cammuni archives. Moreover, these scholars wrote about the Jews without connecting them to the Brescian economy. Excluding them in this manner from the historical and social fabric justified the anti-Semitism of the 1500's, a time in which the Jews had been alienated from society. Finally, during the Fascist period, [their studies] served to resuscitate Renaissance anti-Semitism in order to justify the racial laws. The limits of these previous scholars were therefore twofold: a fundamentally anti-Semitic prejudice and an ignorance of Jewish sources."

Don Franco is conversant with more than a dozen languages. In addition to English, Italian, French and German, he has mastered the ancient languages Akkadian, Etruscan, Celtic, Hebrew, Aramaic, Sanscrit, Mycenaean, Latin, and Greek, as well as Cammuni, the ancient native language of the Valcamonica valley in which his family was resident for at least a thousand years. This facility enabled him to etymologically trace the route of the ancient metalworking artisans from the Mesopotamian milieu up the Danube across Transylvania into Central Europe, and down into Valcamonica.

High up on the Valcamonica mountain sides are numerous, expansive bald-faced rocks, covered with thousands upon thousands of engravings, graffiti dating back to 8000 B.C.E. The ancient artists continued this artistic practice for many millennia from the Prehistoric through the Proto-historic, Copper, Bronze and Iron Ages. One of the areas in which great assemblages of engravings are found has been set aside as the National Park of Naquane, with several miles of trails.

The first attempt at a chronological and typograph-ic analysis of the Cammuni rock engravings is credited to the Jewish scholar Emmanuel Anati. The astounding discovery that the Iron Age engravings employed the Etruscan alphabet upset all previous theories on the provenance and areas of settlements of the Etruscans.

The Etruscan alphabet was adapted in the region to the particular phonetic requirements of the language spoken by the Cammunis. Don Franco, as the inhabitants of the region lovingly refer to Father Bontempi, being familiar with both languages, was uniquely able to interpolate this variation. Don Franco identified the Etruscan alphabet as of Semitic origin.

"The arrival of iron workers in Valcamonica," states Don Franco, "can be fixed with precision, taking account of certain archaeological evidence." He goes on to quote Emmanuel Anati, who places the initiation of the Iron Age in the region at 850 BCE. The arrival of ferric technology coincides with the arrival of the Etruscans.

The Iron Age came into being in the Israelite villages springing into existence in the Canaanite hills in the 12th century BCE.3 The Etruscan connection may be, therefore, an intriguing new development, one which may harbor a revolutionary historical impact.

"Considering the movement from East to West and the slowness of the diffusion of the new technology," continues Don Franco, "it can be affirmed that the ironworkers began operations in Valcamonica between the end of the ninth and the beginning of the eighth century BCE, almost a century and a half before [it appeared in] Switzerland."

Etruscan inscriptions dated to about 700 BCE. were recently identified near Como, as well as in other areas of northern Italy.

Industrial and commercial activity spread out from the area between the sixth and fourth centuries. The importance of iron for tools and weapons led to Cammuni contacts with the Myceneans, Celts, Romans and Greeks. An incursion of the Celts led to a period of dominance coinciding with the development of the La Tène culture to the north from about 300 to 189 BCE. Historians had hitherto proposed the initiation of ferric technology in Europe to the area of the La Tène culture. It is now a reasonable assumption that the technology went north from Valcamonica, where it had already been practiced for centuries.

Etruscans and Semites in Valcamonica

The Etruscan inscriptions in Valcamonica helped Don Franco resolve an old mystery. Based on evidence culled from their presence in central Italy, it was widely accepted

that the Etruscans came from Lydia (south-eastern Anatolia) or from elsewhere in the Near East. The Roman historians Livio and Pliny, however, thought they came from the Alpine region. These references and other indications led some archaeologists to propose that the Etruscans and the area's pre-Roman technologies were indigenous to Italy.

Valcamonica's etymological evidence led Don Franco to determine that both the Etruscans and the Iron Age technologies did indeed come from the East, at the same time. Many medieval Cammuni terms derive from the Celtic, Greek, or Latin languages, as can be expected, but Etruscan linguistic roots are particularly discernable in relation to ferric technology.

For example, the ancient regional measure for iron ore, lanxum, is reflected in the name of an area near an ancient mine, Langolina. The measurer of the ore was called Terlengo, a word composed of two parts, ter\leng, and derives from the Etruscan ter\ces\lancum, literally, "the judge of iron measuring."

The Latin language is itself deeply indebted to Etruscan. The transcription process is visible in a reference in a deed near "the property of the Bontempi brothers," referring to "the district of Vitioli, or of the iron furnace,..." Hidden in the Latin terms vitiolum/vitiolo is the more ancient term, visi/ol, a modification of the Etruscan terms for water[power] and fire, the two essential elements for conducting the ferric industry. The exceptional availability of waterpower and of hardwoods for fuel, was the basis for conducting the ferric "waterpower/fire" industry near the iron mines.

"The most ancient linguistic expression for an iron-working shop is verseol, vitiolo: i.e., a furnace near a torrent."

The Etruscan term for "overseer of the forge" is e macstrua; the Latin equivalent is magister e. It reappears in the name Mastalini.

Likewise, the name Salamino is composed of sala/min; sala is Etruscan for "operator," min is Etruscan for "master," ergo: "Master artisan."

Don Franco goes on to analyze scores of other terms in the ancient documents and names of the region, tracing them to Greek, Celtic, Latin or Etruscan origins. Most significantly, he traces many Etruscan and other words of Semitic derivation back to Akkadian origins. Worthy of additional mention here is the designation "artisan" with the use of the Etruscan verb us, i.e.: "to craft." The district Luzzana was originally written as l'Ussana, which in turn was a contraction of the Latin phrase illi ussana ("the artisan district"), which in turn derives from the Etruscan us.

Don Franco also corrects derivations cited by scholars in the past. For example, the regional common name Berzo, also found in the form Berse, was previously assumed to have come from the German Berg ("hill"). Don Franco demonstrates that the name is derived instead from the Etruscan verse\berse: "the site of the furnaces."

The Semitic connection is likewise etymologically apparent. Don Franco notes that the Canaanite (Ugaritic) God-smith, Chuzen, is reflected in the Camunni word for the process of making wrought iron, cuder, literally : "beating iron." The town, Cuzen, and the family name de Cudera are of the same derivation.

Agriculture, albeit limited by the rugged terrain, was nonetheless practiced, and the ethnicity of its ancient immigrant eastern practitioners is likewise reflected in the local dialect. Grain-mills, Caramola in Valcamonica dialect, is composed of cara/mola. Cara derives from the Etruscan root Car, "to build"; mola is Italian for "millstone." The word thus translates to a building containing a millstone.

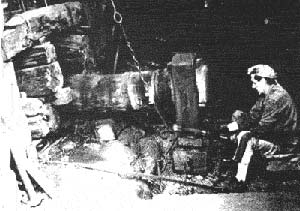

[Left: A step into the Bienno smithies is a step back into medieval times. The forges are powered by huge water-wheels, fed by a viaduct from the Oglio River and geared to 18" diameter logs headed with massive three-foot iron hammers. The artisans turn out farm equipments and other iron artifacts. Some Bienno smithies have been in operation since the 12th century. The iron industry of the region dates back to pre-Roman times. Photo by the author.]

[Left: A step into the Bienno smithies is a step back into medieval times. The forges are powered by huge water-wheels, fed by a viaduct from the Oglio River and geared to 18" diameter logs headed with massive three-foot iron hammers. The artisans turn out farm equipments and other iron artifacts. Some Bienno smithies have been in operation since the 12th century. The iron industry of the region dates back to pre-Roman times. Photo by the author.]Fire and Water: Industry Elements

The presence of iron ore (the only economically viable iron mines in Italy), together with the abundance of wood and waterpower, was the basis of an industry which flourished into the twentieth century. The involvement of Jews in the industry is evidenced by gravestone inscriptions. Another Judaic cemetery, we were grieved to find, lies under Santa Giulia, now the town museum.

The museum is a vast complex of buildings surrounding several courts. They include the church of Santa Giulia, the Basilica of San Salvatore, a monastery, three cloisters, a building called Santa Maria in Solario. Excavations under some of the buildings and in the courts have uncovered the ruins of Roman buildings and traces of the Jewish cemetery.

Jewish presence and activity in Valcamonica prior to the 15th century can be interpolated from distinctly Jewish family names appearing after the time of the Inquisition on gravestones and other memorializing inscriptions in a Christian environment. On the gravestones in the cemetery adjoining one small church, and applied to the wall of the church are the insignia and information about two distinguished families with the surnames David. The family name Simone appears elsewhere, as well as other names indicating Jewish origins.

Iron-working continues in Valcamonica, and is still powered by waterpower. A wooden viaduct follows the Torrente Oglio down the mountain, branching off to turn huge water wheels of a few of the many smithies that once operated in the town, as well as of a grain mill, still grinding out flour with a millstone more than a meter in diameter. The equipment and the handwork in these smithies have not changed over the centuries. A step into these crowded workshops is a step backwards into medieval times.

[Right: The reading room of the Querignano libray in Brescia. The library contains much historically important Judaic material but hitherto has not been delved into by Jewish historians. Photograph by the author.]

The Querigniana Library

A most unusual library, housed in a magnificent building in the heart of Brescia, contains several hundred thousand ancient books and manuscripts. Don Franco Bontempi informed the director of our visit, and we were not only given carte blanche to examine ancient books and texts but personally assisted by the curator of the section devoted to books by and about Jews. We were told that they have rarely been looked into.

The library was founded in 1747. It was opened to the public by Cardinal Angelo Maria Querini, formerly librarian at the Vatican library, and then well known as a bibliophile. He was obviously wealthy, for he had a monumental palace designed and built by the architect Maretti. He launched the assembly of a vast number of ancient scholarly books by donating his remarkable private collection, and by leaving a substantial fund for the expansion of the library. Before his death he passed the administration of the facility to the Brescian town council.

The entrance hall at the top of a monumental staircase is decorated with magnificent frescos painted by Albirizzi and Scotti, and by a bust of the founder sculptured by Callegari. The main reading room, as well as the smaller ones were similarly frescoed and furnished.

It was thrilling indeed to see a printed edition of a book of poetic compositions by Immanuel Ben Salomon, published by Gerson Soncino in 1491, and other texts printed by that famous fifteenth century publishing family of the Brescian area.

Included in the Querigniana collection is a most important series of 34 massive tomes edited by a churchman, Blasio Ugolino, issued in 1744. They contain a compendium of everything known to the church of the times about Jewish customs, laws, institutions, and sacred rites. Written from the church's point of view, and therefore requiring rigid interpolation, the series nonetheless should provide a vast amount of information about Jewish life and history prior to the date of its publication.

The books are written in Latin and contain voluminous quotations from Hebrew texts and documents, some of which have not survived in any other form. The Latin is interspersed heavily with Hebrew and Aramaic quotations on virtually every page.

The Kaufman Collection

A project worthy of further investigation is a most valuable and important collection of Hebrew literature, sold by a Brescian area Jew, Kaufman, to a Hungarian buyer. Father Franco Bontempi, suspecting that much local and other literature of great value had thus left the area, and fearing that it would remain unnoticed, pursued the matter, and located the collection in a Hungarian university's library. He managed to obtain a catalogue listing of the sale.

Well over a thousand ancient books are in the collection, dating from 1477 to the end of the nineteenth century, with a large proportion from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The books were published in virtually every country in which Jews existed. The first 50 books listed, for example, were published in Jerusalem, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Berlin, Warsaw, Cambridge, Constantinople, Venice, Prsemyl, Krakow, Soncino, Vienna, Munich, London, Vilna, Amsterdam and Cleve.

The Gonzaga Connection

The research being followed by Father Franco Bontempi is parallel to that done by me in the adjoining province of Piedmont, where numerous Jewish communities lived in relative security. Casale Montferrato was the administrative capital of the ruling Marquises Montferrato, a family related to the succeeding Gonzaga dynasty. It was the center of Jewish life of the region.4 The continuous existence of a Jewish community in Casale Montferrato as a viable, free community for centuries was unique to Christian Europe. Nowhere in Europe did the Jews experience less persecution than under the Montferrato and successor Gonzaga dynasties. Many Jews enjoyed special privileges at the court of the Gonzagas at Mantua. The exalted position of such Jews was codified by the issuance of a patente di familiare; that gave the recipient the run of the palace and many other important privileges.

The patentes were issued during periods when Jews elsewhere were being expelled, confined to ghettos or subjected to severe restrictions and taxation.

The journals of the Casale Montferrato Judaic community begin in 1589, when the Gonzaga regime granted a large degree of autonomy to the Jewish community of Casale Montferrato. The Jews had enjoyed Ducal tolerance in the area before that time. They had impacted significantly on the cultural, commercial and industrial life of the area since pre-Roman times.

The Gonzagas were named after a small town in the Mantua province. They ruled at Mantua for three centuries, as Marquises from 1432 and as Dukes from 1530. They were always at war with the dukes of Milan, and welcomed the Jews being persecuted in or expelled from Milan. The tenth and last Duke of Mantua sided with the French against the Austrian Emperor Joseph I, and died in exile in 1708.

The Gonzaga court was a beehive of Jewish cultural activity, in which music, theater, science, and literature flourished.

A community of glassmakers was brought from Palestine by the crusading Marquises di Montferrato. They formed a cooperative village in the Montferrato fief at Altare ("High Place"), thereafter referred to as the Università d'Altare. Members of two historically significant Altarese glassmaking families were honored with patentes di familiare at the Gonzaga court: the Dagnias and the Perottos.5

An Oduardo Dagnia and his four sons left Italy to pioneer the art of glassmaking in the Weald, Stourbridge, and Newcastle in England; A Bernardo Perrotto followed his uncle to France, where Bernardo developed a casting system of producing flat glass panels. The ability to produce large panes of flat window glass was a major advance in vitric technology. In 1669 Perotto was granted a royal patent for the revolutionary process. Subsequently Perrotto patented formulas for making opaque white glass (porcelaine en verre), of making red glass (rouge des Anciens). These and other significant break-through won Bernardo Perrotto a well-deserved, permanent place in the glassmaker's hall of fame.

A branch of the Perrotto family emigrated to England, and also played an important role in the development of the Bristol and Stourbridge glass-making industry.

A Jewish metal-worker Salamone de Sessa likewise worked at the Gonzaga court. He was much in demand, and could boast of such other prestigious patrons as Cesare Borgia. Deplorably, Salamone later converted, and became renowned as Ercole de' Fedeli.

The theater and music were integral to life at the Gonzaga palazzo. Jewish actors were famous for their histrionic ability. Dramatic performances in honor of a visiting grandee generally devolved upon Jewish productions. It is reported that performances on Friday had to be performed early enough to end at the Sabbath, and were postponed on Jewish holidays. Among many notable playwrights was the Hebrew poet Leone de' Sommi Portaleone, a prolific writer of prose and verse. On the one hand, he founded the synagogue in near-by Portaleone; on the other hand he wrote non-Jewish plays for the Gonzaga court. In 1556 de Sommi authored Dialogues on the Dramatic Art, the first such work ever written in a European language.

A giant of musical history was Salamone de' Rossi, the inventor of the symphonic musical format Salamone produced both synagogue and secular music, and was the "Beethoven of his times." Salamone had been preceded by an earlier composer known as Giuseppe Hebreo ("Joseph the Jew"), who collaborated at the court of Lorenzo de Medici with the Jewish writer on the art of dancing, Guglielmo da Pesaro. Another of the many singers, instrumentalists and composers was David Civita, whose works were also performed in Venice, and Allegro Porto, who dedicated three volumes of his compositions to Emperor Ferdinand.

It has been documented by a chronicler of the region that the first violin was the product of a Brescian Jew. Violin-making thereafter became a tour-de-force of the nearby town of Cremona, and the violins of Amati (who may have Jewish or of Jewish origin), Stradivarius and other Cremonians are now the avidly sought instruments of the world's great violinists.

The research into and documentation of the extent of those contributions to the industry and culture of the area continues to be an ongoing labor of love by that remarkable scholar, Father Franco Bontempi.

[Left: Gerson Soncino, Meshal ha-qadmoni, wood engraving # 10, "Teaching the Lion." Soncino's allegorical animals expressed opinions that could not be openly aired. In this illustration, the lowly but literate animals teaching the ruling but illiterate lion bears a significance far beyond the simple fable it depicts. Soncino's books are among the earliest ever printed.]

[Left: Gerson Soncino, Meshal ha-qadmoni, wood engraving # 10, "Teaching the Lion." Soncino's allegorical animals expressed opinions that could not be openly aired. In this illustration, the lowly but literate animals teaching the ruling but illiterate lion bears a significance far beyond the simple fable it depicts. Soncino's books are among the earliest ever printed.]Printing and PapermakingNot least of the important cultural attributes of the Brescian region was due to the introduction by Jews in the fifteenth century of printing industries into Mantua, Soncino, Sabbioneta, and Cremona. Near-by Venice, Ferrara, and Parma were likewise the cultural beneficiaries of Judaic printing presses in that early period, as well as other posts in Italy as far south as Reggio di Calabria.

At the outset, the art of printing was mainly a Jewish undertaking, despite the credit given to Gutenberg for its "invention." It is timely to recall, as Cecil Roth reminds us, that "As early as 1444 - six years, that is, before the date generally assigned to the beginning of Gutenberg's activity - an agreement for the cutting of a Hebrew fount 'according to the art of writing artificially,' was entered into at Avignon between a wandering German craftsman and a member of the local [Jewish] community."6 It is obvious that if fonts were already being produced on contract by the Jews of Avignon, that printing had already been invented, and that the Avignon Jews were knowledgeable in the art.

To reinforce that conclusion, we take note of the existence of another pre-Gutenberg "transaction between Procop Waldvogel of Prague and a Jew named David of Calderousse, whereby Waldvogel taught David the science and art of printing, and bound himself to give him 27 matrices for Hebrew letters."7

Gutenberg, although the son of a patrician, started out in Strasbourg as an apprentice goldsmith, generally a Jewish craft. Both Gutenberg and his partner John Fust owe their business to Jews of Enheim, a village in Alsace; they supplied the funds to enable them to establish and conduct their printing business.

It is difficult to determine just where printing was first introduced into Italy. The earliest date registered in a Jewish/Italian printed book is 1475, only 25 years after Gutenberg operated a press. It is evident that printing had been already well under way in Italy for some years before that time. We owe the preservation of the early Jewish printed literature to a righteous Christian, Giambernardo de Rossi of Parma, a professor of Oriental language at Parma's university. David Amram wrote that: "While others pursued gaberdined Jews through hooting mobs... [and] preached from pulpit and rostrum against the perfidious tribe of Israel, de Rossi sat in his library and with loving care, as though himself of the seed of Abraham, studied the words of the sages of Israel. With scholar's care and lover's patience, this noble Christian sought the cradle books of the Hebrew presses... Dying, he bequeathed his books to the Grand Ducal Library at Parma, where among his rare and beautiful Hebraica there lies a time-stained, tear-stained and much mutilated volume, whose one hundred and sixteen pages can tell a tale much sadder than stands printed there in the clear type which Abraham ben Garten ben Isaac set in Reggio di Calabria in 1475."8

It is likewise fitting to recall that printing was made feasible by the use of paper. Jews traveling the "glass, linen, silk and spice route" into the heart of China learned paper-making from the Chinese, and brought the technology to Europe. They established the first paper-making factory in Spain at Játiva, near Valencia.

The Jews began the use of paper by copying their holy literature on the serviceable sheets. This led members of the church hierarchy to suspect paper as a subversive material. The Abbot of Cluny, ("Peter the Venerable," 1092-1158), "recorded his objection to paper as a Jewish production, on which the unbelievers copied the Talmud and other obnoxious literature"9

Judaic history in the region of Mantua and contiguous Brescia extends back into Roman times. The documentation of Jewish presence and activity in the Roman, Middle age and Medieval periods has survived only in bits and pieces. The evidence that did survive pierces the fog of a millennium and a half of Christian obfuscation, and attests to the continuous presence of a significant industrial, scientific and intellectual Jewish community.

For example, we find that Abraham Ibn Ezra (1092-1167), poet, exegetist, and translator of an astronomical work from the Arabic into Hebrew, wrote a grammatical work at Mantua in 1140, three hundred years before the Gonzagas became the Marquises of the city. Ibn Ezra, a restless, brilliant scholar, was unencumbered with worldly possessions, being a poor participant in worldly affairs. He said of himself that if he were to sell candles the sun would never set, and if he were to deal in shrouds, none would die.

"It may be said that [Abraham ben Ezra] created Hebrew prose for scientific purposes... He was a thorough rationalist and believed that a knowledge of grammar was indispensable for the understanding of Holy writ..."10

The Martinengos and the Jews

The tolerance practiced by the Gonzagas was also practiced by the Martinengos, a feudal family of the Brescian region originating from Valle Camonica (otherwise written as Valcamonica). The known history of the Martinengos goes far back into antiquity, extending into the past long before the Gonzagas became the lords of Mantua. It is suspected that the Martinengos may, indeed, have had Jewish roots, for their rise to nobility stemmed from their involvement in the iron industry of Valle Camonica (see Newsletter 68), and may go as far back as the Roman period.

Don Franco discovered an undercurrent of Jewish cultural and technological tradition that predated the advent of the Montferratos and the related Gonzagas relating to the Martinengos.

The family Martinengo of Valcamonica invested their profits gained from iron work in the purchase of land in the valley of the Po River south of Brescia. Father Franco Bontempi found that Jewish tenant farmers were employed on the Martinengo estates during the time when the rest of the Christian world was vehemently persecuting them.. At the time of the Crusades, Valcamonica Jews are recorded to have been long involved in agriculture in the area of the town of Asola, central to the Brescian flatlands. Between 1150 and 1200 a churchman, Arnoldo da Brescia, preached venomously against the Jews, and his exhortations inspired "a little pogrom."11

The records show that, nonetheless, the Jews continued to farm on the Mantinengo fief into the Renaissance period, despite ecclesiastic prohibitions against Jewish land ownership, and despite continuing anti-Semitic fulminations of churchmen. This situation could only subsist under a protective mantle of the local lords.

As the centuries passed, the Martinengos were ennobled as the lords of more than a score of villages on their property. They ruled over an extensive territory; to protect their fief and its inhabitants against marauders and ambitious neighbors, they built several great moat-protected castles, one of which lay between the Jewish communities of Asola and Soncino.

[Right: Gerson Soncino, Meshal ha-qadmoni, wood engraving # 54, "The Book and the Sun." The Soncino woodcutsdepict all aspects of Judaic life. This illustrations attest to advanced astronomical observations as integral to Judaic culture. The paper on which Soncino printed was produced ay nearby Salo, where Jewish entrepreneurs had introduced papermaking.]

[Right: Gerson Soncino, Meshal ha-qadmoni, wood engraving # 54, "The Book and the Sun." The Soncino woodcutsdepict all aspects of Judaic life. This illustrations attest to advanced astronomical observations as integral to Judaic culture. The paper on which Soncino printed was produced ay nearby Salo, where Jewish entrepreneurs had introduced papermaking.]The latter village became famous for the Hebrew press established by a German-Jewish family that took the name of the village, Soncino,.for their own. The family traces its origin to a Moses of Speyer in Alsace, who lived about the mid-thirteenth century. The family was probably among those expelled from Speyer by a general edict in 1435. A Jew known as Moses Mentzlan (meaning "manikin," a rather contemptuous reference to his small stature), fled to the Bavarian city of Furth. Subsequently his son, Samuel, crossed the Alps to settle in the tiny Brescian city of Orzinovi. On May 9, 1454, Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan, issued a patente granting Samuel and his family permission to settle in the fortified city of Soncino and to open a bank. Samuel's son, Israel Nathan Soncino, helped his father in business but took up the practice of medicine. In 1480, he turned his talents to the art of printing, and founded a press which became renowned the world over.

The Martinengos also had several town palazzi in the city of Brescia itself; they are now public buildings that retain muraled walls and ceilings executed by renowned artists, superb examples of structural and architectural craftsmanship. A twelfth century Martinengo building, an earlier and far more modest family dwelling, is located in a small village near Brescia and is now a kindergarten.

The difference between the treatment of the Jews by the Martinengos, Gonzagas, and Montferratos, and that of the Jews in the adjoining virulent Christian environments, is dramatically illustrated in two towns on either side of Lake Garda. On the western shore, nested along an expansive bay of the beautiful lake, a Jewish community flourished at Saló. The Jews thrived in the lucrative paper industry they had introduced there into Italy. One of the earliest town documents, drawn in 1320, records the sale of a handwritten bible by the scribe, Mosè ben Abraham Sefardi. The paper industry gained commercial importance as Jewish printing presses sprung into being throughout the area as far as Venice. Saló was the home of Nathan, the renowned poet, and of other scholars through the ages. The town is currently an outstanding resort, frequented mainly by appreciative Austrian and German sun-worshipers.

Directly across Lake Garda, the town of Trento became infamous for accusations of the practice of infanticide in the conduct of Jewish ritual. The malignant accusations were launched by Simonino da Trento in 1475, and thereafter echoed throughout Christendom. It was the town in which the equally notorious Council of Trent, in session from 1545 to 1563, launched the Counter-Reformation and codified antisemitism into church dogma.

In further contrast, let it suffice to mention that soon thereafter, in Mantua from 1573-1575, Azariah dei Rossi (1514-1578), was free to publish his work, The Light of Eyes. "This scholar was far ahead of his times" affirm Margolis and Marx, "in applying scientific method to Jewish literary and historical questions."12

To the southeast lay the duchy of Ferrara, ruled by the House of Este. Hercules I (1471-1505), extended a welcome to twenty-one Jewish families in the very year they were expelled from Spain. "The immigrants took an active part in developing the commerce of the city... they had their own separate organization with synagogues, rabbis, school and burying ground... In 1531 the German Jews added their own synagogue, in addition to the Sephardic and native-Italian houses of worship."13

The renowned Judaic historical figures, Joseph Nasi and his aunt Gracia and many other notables found refuge in Ferrara. The city continued to be a bulwark of religious liberty until the Estes dynasty was extinguished.

The benign climate of tolerance in Ferrara did not last. In 1597, the duchy was added to the Papal states. When the new administrator, Cardinal Aldobrandini, entered the city, he was greeted by a populace shouting, "Down with the Jews." Over half the Jews fled to Venice, Modena, and Mantua.

Venice, in turn, recurrently expelled the Jews, and the area under the Gonzagas and Martinengos again provided convenient refuge. Glassmakers left the Venetian glassmaking island of Murano in these traumatic times to establish themselves in the Università d'Altare, where the glassmaking community had been brought from Palestine by a Gonzaga antecedent, the Marquise de Montferrato.14

To the west Jews were persecuted and expelled at various times by the Milanese overlords. They likewise found a safe harbor in the Gonzaga fief until they could determine where they could best find peace and freedom.

In the critical period from 1490 to 1591, Valcamonica played host to outstanding Jewish entrepreneurs and scholars from elsewhere in Italy. Many settled in Verolanuova, a charming little town along the Oglio river in the heart of Valcamonica. The famed Abraham Finza was among those who spent more than a score of years in the Alpine village. His correspondence with Lucrezia Gonzaga about the plight of the Jews expelled from Spain and other matters is most revealing.

Leone Bassano and Leone Soave were other Judaic notables who established themselves and their families in the little Alpine town.

Bandiera Rosso; Bandiera Verde

Valcamonica has a longstanding tradition of resisting tyranny. The peoples of the valley were the last of Italy to submit to Roman hegemony. They were among the last to come under church dominance. Throughout the centuries in which powers on every side vied for control over the valley's iron resources and its valuable arms and tools industries, they maintained their dialect, customs and as much independence as circumstances allowed.

The racial laws ignominiously installed in Italy by Mussolini in cowtowing to Hitler's dictates were almost universally ignored in Valcamonica. The incursion of Nazi Germany's armed forces sparked fierce resistance. Young people from the valley's towns fled to mountain hideouts, from which vantage they harassed the German outposts and lines of communication.

Jews were hidden, and many joined the partisans. Among them was a Jewish attorney, Levi Sandre, Levi joined the partisans, welded the scattered, unorganized resistance into a cohesive fighting force, and, as their commander, led them in successful engagements against Nazi contingents. After the war, Levi became a magistrate, and finally a member of Italy's Supreme Court.

Politics were set aside during the Nazi occupation. The left-orientated partisans, under their red banner (the Bandiera Rosso), and the center/right partisans, under their green banner (the Bandiera Verde), cooperated in their common interest during those difficult times. Pauline and I were bemused by a heated argument between veterans of the two groups on which group had more diligently hidden out the community's Jews! The exchange took place at the grave sites of the partisans who had fallen in battle.

The partisans were buried high atop an Alpine peak near one of their hideouts, where a commemorative ceremony is held each year. The precipitous, snow-covered peaks that had borne witness to the heroic stand of the partisans, stand again in silent witness of this annual event. The surviving veterans, now grey-haired, dress in Alpine shorts, an eagle's feather raking defiantly backward from their peaked hats. They line up on either side of the grave sites, the Greens on one side, the Reds on the other.

A mass was held, followed by an oration by the valley's historian, a retired professor, who went on at length about the valley's tradition of resistance to tyranny and the need for being ever vigilant against new forms of tyranny. Don Franco had arranged for me to represent the Jews on this occasion. In my address I thanked the partisans who had fallen and those who survived on three accounts: as a human being, as a Jew, and as an individual who had lost 35 members of his family in the holocaust.

After the ceremony, a dinner with a most remarkable menu was held in the City Hall of the town. Polenta, potatoes, local herbs, and a sausage made largely of non-meat fillers were served, the foods that were consumed by the partisans in their sojourn in the mountains.

Much research remains to be done in this region of Italy, so rich in traces of the Judaic imprint. Don Franco's command of indigenous and derivative languages, his intimate knowledge of the area, his familiarity with and access to archival material, his passionate and untiring devotion to the reconstitution of his own ancestral heritage, make him uniquely positioned to pursue that work. He deserves the full-hearted support of the Jewish community.

Notes

The facts regarding Brescia, the Etruscans and the Martinengos were derived from three of Father Franco Bontempi's books, and are too numerous to be annotated:

Ferro e Stella, printed in two editions, one complete and the other employed as a catalog of and reference material for the expositions assembled by Bontempi and at which he lectures. The subtitle translates to"Jewish Brescia in the Renaissance Italy."

Bienno, History, Society, and Economy, elaborates Bontempi's theory on the introduction of Iron Age technology into the region of by peoples from the East.

Economia del Ferro, research on the history of the iron industry in Valcamonica from the 15th to the 19th century.

[Left: One of the Martinengo castles south of Brescia, dating to the 14th century. The Martinengos were neighbors of the Gonzagas at near-by Mantua. Jews farmed in the Martinengo fief, and introduced printing at Soncino, a few miles west of the castles. Jews enjoyed a tolerance unique to Christian Europe under the Martinengos and the Gonzagas, and contributed vastly to the region's economy and culture. Father Franco Bontempi's research has gone far to illuminate this important facet of European and Judaic history. Photograph by the author.]

[Left: One of the Martinengo castles south of Brescia, dating to the 14th century. The Martinengos were neighbors of the Gonzagas at near-by Mantua. Jews farmed in the Martinengo fief, and introduced printing at Soncino, a few miles west of the castles. Jews enjoyed a tolerance unique to Christian Europe under the Martinengos and the Gonzagas, and contributed vastly to the region's economy and culture. Father Franco Bontempi's research has gone far to illuminate this important facet of European and Judaic history. Photograph by the author.]1. HHF Fact Paper 28, The Jews of Aquileia

2. HHF Fact Papers 15, Silkmaking and the Jews, and HHF Fact Paper 3, The Silk Route; A Judaic Odyssey.

3. HHF Fact Paper 4, Iron-working; a Judaic Heritage.

4. HHF Fact Paper 24, The Jews of Casale Montferrato

5. HHF Fact Paper 25, The Glassmakers of Altare.

6. Cecil Roth, The Jewish Contribution to Civilization, 49.

7. Amram, The Makers of Hebrew Books in Italy, 15.

8. David Amram , Ibid., 23-24.

9. Roth, Ibid., 50.

10. Max L. Margolia and Alexander Marx, A History of the Jewish People, p. 333.

11. Bontempi, Il Ferro e la Stella XVII.

12. Margolis and Marx, Ibid., 503-4.

13. Margolis and Marx, Ibid., 503.

14. HHF Fact Paper 25 ,The Glassmakers of Altare

No comments:

Post a Comment